The article analyzes the erosion mechanisms of refractory bricks in various sections of the working lining of refined steel ladles and proposes an optimized design. Results indicate: 1) Selecting electrofused magnesia with large crystals strengthens the matrix of magnesia-carbon bricks, enhancing their erosion resistance; introducing asphalt-modified phenolic resin improves the thermal spalling resistance of magnesia-carbon bricks; adding an appropriate amount of β-Si₃N₄ helps suppress graphite oxidation and slag penetration, enhancing slag resistance. 2) Incorporating fine alumina powder, fine magnesia-alumina spinel powder, and composite additives effectively prevents longitudinal cracking caused by widening gaps between magnesia particles and graphite in joint bricks. 3) Magnesium-aluminum carbon bricks demonstrate superior erosion resistance as the “lower slag line” compared to aluminum-magnesium carbon bricks. 4) The optimized ladle working lining lifespan increased from 39 ladles to over 46 ladles, effectively reducing refractory consumption per ton of steel.

炼钢厂采用EAF→LF→VD→CCM冶炼工艺,在钢包内进行电极加热、吹氩搅拌、造渣、合金化、真空处理等一系列冶炼过程。随着对钢的品质要求越来越高,钢包的吹氩搅拌时间、LF加热时间、VD高真空时间皆延长,导致钢包工作衬使用环境进一步恶化,钢包包龄偏低,钢包耐火材料消耗偏高。因此,优化改进钢包工作衬以提高钢包包龄,对于钢包安全运行以及降低耐火材料消耗有积极意义。

Analysis of the Causes of Damage to Magnesium-Carbon Bricks in Different Areas of Refined Steel Ladles

The refractory lining repair pattern for ladles in Zone 2 is as follows: Replace the slag line bricks once during the mid-service period of the ladle. After cooling off-line, remove the entire working lining and install a new one. Through tracking ladle usage and measuring residual brick thickness during removal, the most severely eroded areas of the working lining are primarily near the sixth layer of slag line bricks, with residual thicknesses of 60–70 mm, and in severe cases less than 50 mm. Erosion of the ladle wall bricks is also significant, particularly the three layers of working lining bricks adjacent to the ladle bottom, where residual thickness ranges from 70–80 mm. The residual thickness of transition bricks below the slag line was 100 mm, but longitudinal cracks were present. The impact zone at the ladle bottom suffered severe erosion due to high-temperature molten steel impact, with steel inclusions observed within the cracks.

1.1 Erosion of Magnesium-Carbon Bricks in Ladle Slag Line

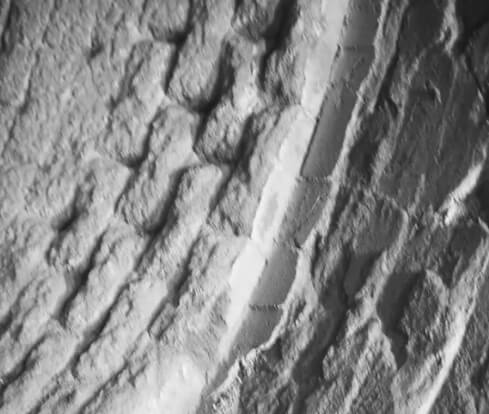

The slag line section of the ladle is made of magnesia-carbon material. In addition to mechanical erosion caused by the agitation of molten steel within the ladle, the slag line bricks also undergo chemical corrosion from the slag. The typical refining slag composition (w) in Zone 2 is: Al₂O₃ 18%–22%, SiO₂ 10%–15%, CaO 45%–55%, MgO 9%–12%; m(CaO):m(SiO₂) ratio is 3.0–4.5. Graphite within the bricks undergoes decarburization reactions with slag and ambient oxygen (C + CO₂ → 2CO, C + FeO → Fe + CO), forming a decarburized layer on the magnesia-carbon brick surface. This increases porosity on the working face, allowing slag to penetrate the decarburized layer and react with the magnesia. Large amounts of SiO₂ and CaO in the slag invade the boundaries of the periclase crystals, forming a low-melting-point liquid phase that flows into the slag along with the periclase [1]. Bottom argon blowing intensifies mechanical erosion while accelerating the destruction of the decarburization layer, creating a cyclic process of oxidation-decarburization-erosion that continuously erodes and thins the magnesia-carbon bricks. Figure 1 shows a photograph of typical erosion at the slag line region.

In the refining ladle furnace, processes such as desulfurization, deoxidation, and alloying of molten steel are carried out. Considering temperature drop during tapping, the tapping temperature is significantly higher than the pouring temperature, typically ranging from 1640 to 1660°C. Simultaneously, during heating in the ladle furnace, the working lining near the arc zone is continuously subjected to high-temperature impact, with localized areas reaching up to 1800°C. Under these high-temperature conditions, prolonged refining duration increases the erosion of refractory materials by molten steel and slag.

During VD vacuum and high-temperature processing, most oxides evaporate and are lost, degrading the structure and properties of refractory materials. This leads to reduced bulk density, increased porosity, and diminished strength [2]. In Zone 2 refining furnaces of steel plants, vacuum levels can reach 67 Pa or lower, with processing times extending to 20–30 minutes. Under these conditions, magnesium-carbon bricks undergo intense redox reactions: MgO + C → Mg + CO. This leads to a loosening of the brick’s microstructure and a sharp decline in strength.

1.2 Cracking of Ladle Joint Bricks

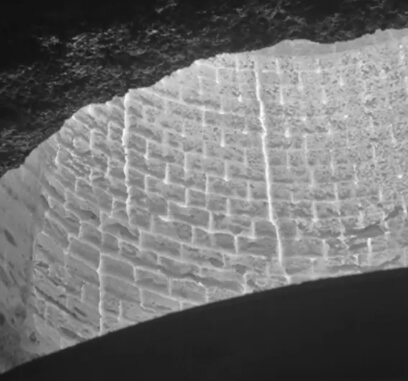

During the mid-to-late stages of ladle usage, longitudinal cracks began appearing in the joint transition bricks. After 35 furnaces, the longitudinal cracks in the ladle walls significantly widened and lengthened. In some ladles, longitudinal cracks exceeded 2 meters in length, with widths over 10 mm and depths exceeding 80 mm, totaling 5 to 6 cracks. Figure 2 shows a photograph of typical cracking in the joint bricks.

The primary causes of longitudinal cracking are as follows: First, the LF furnace undergoes frequent and prolonged electric heating cycles with significant temperature increases, coupled with VD high-vacuum treatment, which causes substantial damage to the structural integrity of the joint bricks. Second, the magnesium carbon bricks themselves exhibit a large difference in thermal expansion coefficients between magnesite and graphite. This disparity leads to inconsistent thermal expansion between magnesia particles and graphite, resulting in widening and continuous propagation of cracks. Third, the rapid thermal cycling during the reintroduction of ladles after replacing slag line bricks mid-use further exacerbates crack formation.

1.3 Ladle Lining Brick Erosion

During use, magnesia-alumina-carbon lining bricks undergo decarburization reactions that form decarburized layers. This increases porosity on the brick’s working surface, allowing slag to penetrate the decarburized layer and react with the matrix. Simultaneously, magnesia reacts with alumina to form magnesia-alumina spinel, causing volume expansion that generates numerous microcracks in the matrix. These cracks progressively expand with repeated thermal shocks during operation, allowing slag to invade the brick interior. Reactions between slag components (CaO, SiO₂, FeO) and matrix constituents (Al₂O₃, MgO) form low-melting-point compounds, accelerating brick erosion—particularly in the bottom three lining brick layers. Since molten slag remains in the ladle for a period after continuous casting completion until slag tapping, these layers experience prolonged contact with slag, resulting in more severe erosion. Slag penetration into refractories not only promotes chemical loss of refractory constituents into the slag but also accelerates structural spalling and deterioration. Typical erosion of ladle wall bricks is illustrated in Figure 3.

1.4 Erosion in the Impact Zone of Ladle Bottoms and Steel Drilling

After 30 furnaces of use, concave pits commonly form in the impact zone of ladles. In some cases, the thinnest point in the impact zone of the ladle bottom measures only 40–50 mm, significantly increasing the risk of ladle perforation and molten steel leakage. Analysis revealed that the load-bearing softening temperature of the bricks in this area is approximately 1600°C, while the tapping temperature for most steel grades in Zone 2 is around 1650°C. This indicates that the high-temperature performance of the refractory materials in this section is insufficient, resulting in inadequate resistance to the erosion of high-temperature molten steel. During the later stages of use, cracks in the impact zone bricks significantly widened. This was primarily due to thermal cycling inducing cracks in the ladle bottom bricks, allowing slag and molten steel to infiltrate along these fissures, leading to structural spalling of the bricks. Particularly in the middle to late stages, the thermal expansion of the magnesium-aluminum spinel carbon bricks gradually decreased, causing the joints between bricks to widen. Molten steel infiltrated through these joints, resulting in steel leakage. Methods such as oxygen purging and wet refractory repairs further exacerbate damage to the impact zone. Figure 4 shows a photograph of typical damage in the impact zone area.

2.Optimization Measures for Ladle Working Lining

2.1 Slag Line Magnesium Carbon Bricks

To address issues such as uneven erosion and insufficient residual thickness of slag line bricks in ladles, a novel modified slag line brick was developed and tested in field trials. The measures implemented were: 1) Maintaining the magnesium-carbon composition of the slag line bricks while selecting electrofused magnesia with large crystals; simultaneously ensuring a calcium-to-silicon mass ratio ≥2 to reduce the reaction between MgO volatilized under high-temperature vacuum conditions and carbon, thereby strengthening the matrix to enhance the brick’s erosion resistance. 2) Introducing asphalt-modified phenolic resin to create a finely interlocked carbon-bonded structure, thereby enhancing the brick’s resistance to spalling [4]. 3) Incorporate an appropriate amount of β-Si₃N₄ to enhance high-temperature flexural strength, reduce thermal expansion, and improve slag erosion resistance. Additionally, a silicon-rich layer formed between the reaction layer and the original brick layer was observed, which helps suppress graphite oxidation and slag penetration [5].

2.2 Jointing Bricks and Wall-Cladding Bricks

By incorporating appropriate amounts of fine alumina powder, fine magnesia-alumina spinel powder, and composite additives into the magnesium-carbon brick formulation, the micro-expansion generated when alumina powder reacts with magnesium oxide in the matrix to form spinel is utilized. This reduces the gaps that develop in the original magnesium-carbon brick structure during use, preventing the expansion of these gaps and the resulting longitudinal cracking.

Magnesium-aluminum carbon bricks incorporate pre-synthesized spinel into fused magnesia. Leveraging the significant difference in their expansion coefficients, microcracks form during temperature changes to relieve thermal stress and mitigate thermal spalling [6]. Compared to aluminum-magnesium carbon bricks, magnesium-aluminum carbon bricks contain higher magnesium oxide content. This excess MgO forms a periclase-spinel structure, Graphite carbon atoms are interleaved within this structure. Given graphite’s high surface tension and low contact angle, it effectively prevents slag penetration. Consequently, these bricks exhibit superior high-temperature performance compared to the alumina-magnesium carbon bricks used in Table 2. Therefore, magnesia-alumina carbon bricks are selected for lining the lower molten pool region of the crucible wall. Their effectiveness in resisting slag erosion in the “lower slag line” area surpasses that of alumina-magnesium carbon bricks.

2.3 Ladle Bottom Impact Zone

To address issues such as molten steel penetration and erosion in the impact zone beneath the lining, we have implemented two key optimizations. First, we have enhanced the original magnesia-alumina spinel carbon brick formulation by incorporating fine magnesia-alumina spinel powder and composite additives. This modification induces micro-expansion in the bricks, elevating their load-bearing softening temperature and thermal shock resistance. Consequently, erosion and penetration by molten steel and slag are suppressed, reducing brick spalling and preventing molten steel from infiltrating through joints. On the other hand, the dimensions of the bottom lining bricks were optimized by reducing the formed thickness from 155mm to 77.5mm. This change was necessary because thicker bricks tend to exhibit uneven bulk density and strength between their top and bottom surfaces. Additionally, thicker bricks have greater taper, resulting in wider joints during installation, which exacerbates steel penetration and drilling phenomena.

3. Optimizing the Application Effectiveness of Refining Ladles in Work-in-Progress

After optimizing the working lining, the erosion resistance of the slag line area and ladle wall bricks has significantly improved. The residual thickness of the test slag line bricks exceeded 120 mm, while that of the test ladle wall bricks exceeded 100 mm. The issue of longitudinal cracking in joint bricks has been markedly reduced, and steel penetration cracks in the ladle bottom impact zone no longer occur. Prior to the lining optimization, the maximum service life of ladles was 39 furnaces. After optimization, the maximum reached 47 furnaces. Following the continuous operation of the optimized ladles, the average monthly service life in Zone 2 reached 46.3 furnaces. Figure 5 shows a photograph of the working lining after the test ladle completed 45 furnaces.

4.Conclusion

(1) Selecting electrofused magnesia with large crystals can reinforce the matrix of magnesia-carbon bricks and enhance their erosion resistance. Introducing asphalt-modified phenolic resin improves the thermal spalling resistance of magnesia-carbon bricks. Adding an appropriate amount of β-Si₃N₄ helps suppress graphite oxidation and slag penetration, thereby increasing the bricks’ slag resistance.

(2) Adding appropriate amounts of fine alumina powder, fine magnesia-alumina spinel powder, and composite additives can effectively prevent longitudinal cracking caused by widening gaps between magnesia particles and graphite in joint bricks.

(3) For Zone 2 refining slag systems, magnesia-alumina-carbon bricks demonstrate superior erosion resistance as the “lower slag line” compared to magnesia-alumina-carbon bricks.

(4) The optimized ladle working lining life increased from 39 ladles to over 46 ladles, effectively reducing refractory consumption per ton of steel.